A Writing Craft All-Star to Beat the Blahs

Ever write a scene and it just feels blah? You know it could be good, but it’s missing something. Or, actually, missing a LOT. After struggling with a few of the scenes in my most recent draft, I decided to revisit Robert McKee’s Story: Substance, structure, style, and the principles of screenwriting (my edition published 2014 by Methuen but you can find the U.S. edition here). McKee’s excellent volume is part of my Writing Craft All-Stars shelf.

Useful for Readers/Observers As Well

If you aren’t a writer but consider yourself more of a reader/observer, the process of scene analysis is still valuable. You can use it to try to understand why a scene in a movie or TV show (or book, etc.) works or doesn’t work for you. In other words, if you liked (or disliked) something, maybe it’s because the scene is flat or there’s no change in value (more on this below). This allows you to be more of a critical reader/viewer, rather than just a passive observer.

Location, Value, and Conflict

Despite the fact that I have McKee’s template of Location, Value, and Conflict in the notes section of every scene I set up in Scrivener, it’s not that easy to keep all the balls in the air while I’m juggling…er, writing. Add text and subtext to the mix and, well, good luck. Quite frequently I start writing and everything that happens to the characters is too easy – there’s no pain, no struggle. This is how you want things to be in real life but in a story, this is a killer. As McKee says, if two lovers look into each other’s eyes, enraptured, say “I love you,” and “mean it” (his italics), then “This is an unactable scene and will die like a rat in the road.” (page 253). Sadly, I fear I have quite an inventory of dead rats lying around in the things I’ve written.

Make a Scene Give Up its Secrets

Lucky for us, McKee outlines a process to help “make a scene give up its secrets” (page 257). Although his book refers to screenwriting, the principles still apply to writing a book. After all, as I said up above, if everything always goes your character’s way, we, your readers, will be missing one of the key things that keeps us wanting to read a story, even if we don’t understand or realize that it’s the conflict that keeps us wanting more (if you’re writing or reading anecdotes, well, that’s a different thing).

According to McKee, in order to analyze the scene properly, we need to:

- Define the conflict

- Note the opening value

- Break the scene into beats

- Note the closing value and compare it with the opening value

- Survey the beats and locate the turning point

Let’s take the following brief exchange between Polly, a parrot, and Gilda, her owner (apologies to McKee as this simple example is mine and mine alone):

Polly: “Polly wants a cracker.”

Gilda: — (doesn’t respond, is lost in thought, a smile on her face)

Polly: “Polly wants a cracker.”

Gilda: “Quiet, Polly.”

Polly: — (quiet for a few seconds)

Gilda: — (relaxes)

Polly: “Polly wants a cracker.”

Gilda: “Shut up!”

Polly: “You’re mean.” Squawk!

Gilda: “Oh, alright! Here’s your cracker.” (gives Polly a cracker)

Define the Conflict

When we define the conflict, you have to ask who it is that’s moving things forward in your scene. In this case, Polly is moving the action forward. She starts out stating she wants something. Each time Gilda responds or ignores her, Polly continues pushing. In the end, it is her actions that force (convince?) Gilda to give her what she wants.

What is it the character wants? McKee recommends framing this as an infinitive: Polly wants to get a cracker (Why? Polly’s hungry. Polly’s bored. Polly’s a PITA. There could be a million reasons.). Who or what is the antagonist in the scene, and what do they (or it) want? Frame this as an infinitive, too: Gilda doesn’t want to give Polly a cracker (Why? She’s busy. She thinks Polly eats too many crackers. She doesn’t want to give in to Polly’s request.).

As McKee points out, your scene protagonist and antagonist should be in direct conflict with each other – the conflict shouldn’t be tangential. Although McKee doesn’t state this in his chapter on scene analysis, it is my understanding that the reasons for the conflict might be tangential. But a direct conflict between the protagonist and antagonist is still there. Polly wants a cracker. Maybe Gilda doesn’t care one way or the other whether Polly gets a cracker but she has some other goal in mind which impedes Polly’s getting the cracker.

Note the Opening Value

McKee gives opening values to the scene like “freedom,” “hope,” “love,” and so on. Regardless of the value expressed, it will either be positive or negative. In reflecting on how I’ve expressed these values in my own scenes recently, I have to admit that I’ve simply given them a “positive” or “negative” symbol, which is not really what McKee suggests (although doing this at least points out whether there has been a change at the end of the scene, which we’ll get to in a moment). In the case of Polly and the cracker, the opening value could be expressed as something like “hunger” or “hope.” Let’s go with “hunger.”

Break the Scene Into Beats

McKee defines a beat as “an exchange of action/reaction in character behavior” (page 258). He advises us to identify what a character is doing, not literally, but what they are really trying to do when they say something or act a certain way. This is your text versus subtext. As he says, if the scene is really what the scene is about, then something needs to change (dialogue shouldn’t be on the nose, etc.). He then says to assign a gerund to this behavior (he gives a really clear example of this in the scene in Casablanca where Ilsa and Rick talk to each other and the linen vendor at the market).

In the case of Polly, she’s asking for a cracker. The subtext in her case, if we want to look beyond just wanting a cracker because she’s hungry, is that she’s controlling Gilda’s behavior (or trying to). By the same token, if Gilda says no, she’s refusing. If she says nothing, that’s still a reaction, ignoring.

So our beats in the above could be written out as:

Beat 1: asking/ignoring (Polly’s action/Gilda’s reaction)

Polly: “Polly wants a cracker.”

Gilda: — (doesn’t respond, is lost in thought, a smile on her face)

Beat 2: asking/denying (Polly’s action/Gilda’s reaction)

Polly: “Polly wants a cracker.”

Gilda: “Quiet, Polly.”

Beat 3: waiting/relaxing (Polly’s action/Gilda’s reaction)

Polly: — (quiet for a few seconds)

Gilda: — (relaxes)

Beat 4: insisting/rebuking (Polly’s action/Gilda’s reaction)

Polly: “Polly wants a cracker!”

Gilda: “Shut up!”

Beat 5: accusing/capitulating (Polly’s action/Gilda’s reaction)

Polly: “You’re mean.” Squawk!

Gilda: “Oh, alright! Here’s your cracker.” (gives Polly a cracker)

Note the Closing Value and Compare it with the Opening Value

You can see that the first time Polly asks for a cracker, the value is hunger, which is negative. But at the end of the scene, Polly receives the cracker, so we can say the value is satisfaction (we could also say it’s satisfaction if her original value was wanting to control Gilda’s behavior). Satisfaction is a positive value, and is therefore the opposite of the starting scene value. As McKee points out, if your starting and ending scene values don’t change, then your scene is a non-event (page 259).

Maybe you are trying to give the audience information in the form of summary (condensing some time period) or exposition (providing context, commenting on events), but if you have an action scene where the value doesn’t change, then it’s flat and won’t work. Remember above when I said we could choose “hunger” or “hope”? If we had assigned Polly’s value as “hope” — Polly has hope that Gilda is going to give her a cracker because when she’s asked for one in the past, she’s gotten one — there would have been no change during this scene. Our scene would’ve been as flat as the cracker Polly is asking for.

Survey the Beats and Locate the Turning Point

Survey the beats and locate the turning points? What about turning the beat around? Time for a break with Vicki Sue Robinson.

Where was I? Right, locating a turning point. According to McKee, once we have our list of beats, we should review them and locate the moment when things change. This is the moment when the values shift from what they were at the beginning of the scene to what they are at the end. In our Polly/Gilda example, the turning point is when Gilda capitulates. This is the moment when everything changes, and the value for Polly changes from negative to positive (she has a cracker, so she’s happy). Note that it is also the exact moment when Gilda’s values change, too, but in her case the change is from positive to negative (she was happy at the beginning of the scene, but now she feels like she gave in to Polly’s screeching). The arc is complete.

Text vs. Subtext

McKee goes into more detail regarding subtext, which is a little difficult to find using my simple example. However, as I said before, even our simple scene needs to be about more than a cracker for it to really work. If we want to get inside Polly’s mind and make her more of an evil parrot, one who is always trying to control Gilda’s actions, then we can say that the subtext of her cracker request is wanting to control Gilda’s actions. And Polly succeeds because Gilda does, indeed, capitulate. Meanwhile, for Gilda the subtext is not wanting to be controlled by her evil parrot but in our example she doesn’t get what she wants at the end of the scene.

Make a Course Correction by Changing Behavior

What can you do if you read through your scene and don’t find a change in value by the time you get to the end? Maybe things happen in your scene but the values don’t change. You also see no clear turning point in your beats. A course correction by changing behavior on the part of your protagonist, antagonist, or both, is in order. Think about what you could have your protagonist say or do that would drive the action forward more. Or have your antagonist do exactly the opposite of what you had in mind when he, she, or it responds to the protagonist. Remember, you don’t want things to be easy for your characters.

You Don’t Even Need to Write the Whole Scene

With the scene I’m working on at the moment (that is, the one I’m NOT working on right now because I’m writing a blog post about how I’m supposedly working on a scene), I’m focusing on defining the conflict and noting the opening and closing values. I haven’t written enough yet to really have a list of scene beats. But I know that the opening value is the same at the beginning and end of the scene. My character gets what she wanted at the beginning of the scene. Therefore, the scene fails. And I can tell this just by imagining (or writing) the very beginning and the very end of the scene. I don’t even need to write the whole scene.

By the same token, if your scene value constantly stays the same as the scene progresses, then you have problems there, too. If all’s well at the beginning of the scene and everything is still coming up roses at the end (in the swell, positive version, not the dark, suffocating stage mother sense), then you can pull out the CLOSED sign and go home. Ditto for a scene where everything is terrible at the start and still terrible at the end. Something has to change both as your scene progresses along with the opening and closing values.

Worth Having On Your Shelf

I highly recommend you find and buy a copy of McKee’s book as it’s definitely worth having on your shelf. My simplistic example doesn’t do the process he details in his book justice. He provides many detailed examples from classic films (often a better way to analyze scene since it takes a lot less time than reading a book). For example, in the chapter on scene analysis he discusses Casablanca and Through a Glass Darkly.

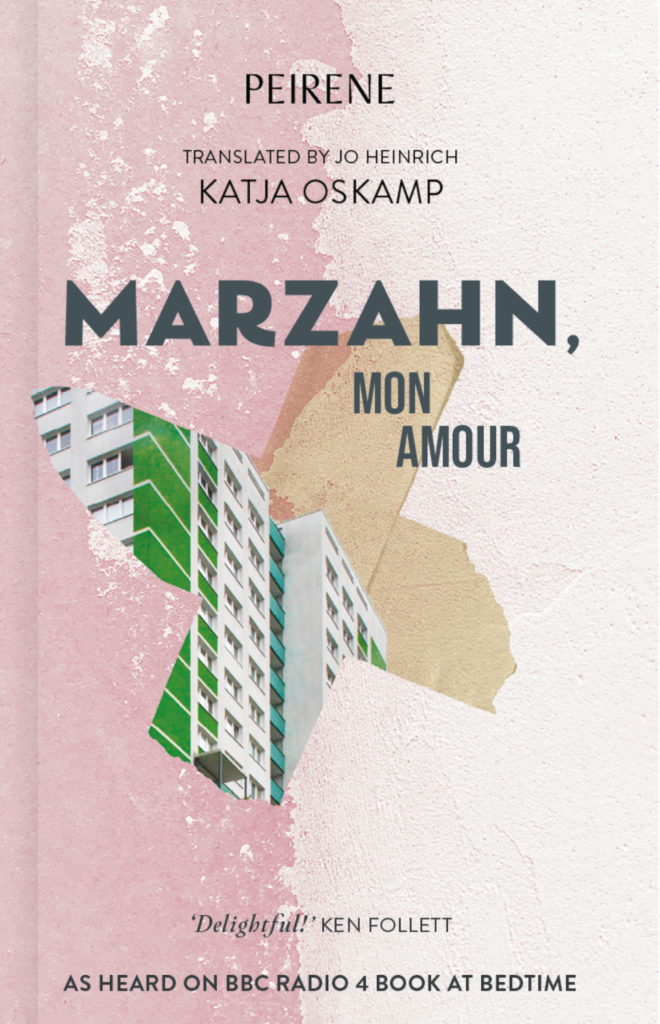

In Other News – Marzahn, Mon Amour

I was really pleased to see that Marzahn, Mon Amour, by Katja Oskamp, won the 2023 Dublin Literary Awards on May 25. Published by Peirene Press (pronounced “pie-ree-knee”), it was translated from the German by Jo Heinrich, who shares in the prize. Oskamp took personal recollections from her time working in a podiatric clinic in the Berlin suburb of Marzhan and weaved them into this collection of delightful, fictional vignettes. The stories are a mix of nostalgic and lighthearted moments. Peirene Press is one of my favorite small indie publishers, specializing in novellas that can be read in “one sitting.” I’m a slow reader so I can’t necessarily finish these books in the two to three hours that they call “a sitting,” but I like the concept. Until Brexit, I belonged to their subscription service, and looked forward to the quarterly editions. Sadly, between the enforcement of customs fees and postal service charges, those deliveries were something I decided to forego.

While I’m on the topic of Peirene Press, I would like to recommend two of their other titles: Snow, Dog, Foot, by Claudio Morandini (translated from the Italian by J Ockenden) and Nordic Fauna, by Andrea Lundgren (translated from the Swedish by John Litell). Well worth reading.

For more writing craft, along with a serving of inspiration, check out my post on Amy Wallen’s How to Write a Novel in 20 Pies.

Pulling at Threads is my occasional newsletter. It always accompanies my blog posts but I sometimes send infrequent updates on other goings on. If you want more of an “insider’s” view on what’s happening in my reading and writing life, you can sign up here.